One of the most difficult skills to learn as a software developer is understanding code. Almost all of our education, training and experience involves solving complex or interesting problems, understanding and meeting customer needs, and architecting good solutions, but nobody teaches you how to pick up where someone left off.

Sooner or later, you're going to be faced with undocumented code, which may have been written by someone that in your opinion should reside in an asylum. This could be a long-departed colleague, or it could have been yourself six months ago.

The study of existing code is often referred to as Software Archaeology, and as analogies go, it's a pretty good one. There's no magic formula, but as with material archaeology, there are methods and tools that can help.

Why is this even necessary?

Best practise when developing software involves solid design, using appropriate building blocks, writing tests, and of course a mixture of both technical and user-facing documentation. Code should be well-factored, appropriately commented and self-documenting as far as possible. There should be a knowledge-base of problems and solutions to help support customers.

Even if your company tries (and maybe even succeeds) at all of these things, there are lots of ways you might end up inheriting someone else's code:

- Your company could take over a competitor's contract.

- A customer might report a bug in an otherwise perfectly functioning system that hasn't been touched for 10 years and pre-dates current working practice.

- You end up supporting someone's hobby project or training project as a real product.

- You rely on an open source library and it stops being maintained, so you have to step up and do it yourself.

In all of these situations, there's a non-trivial chance that the original developers won't have been as diligent as you hopefully are. You may find missing (or worse, poor quality) comments, documentation and tests. You may not fully understand how the code works, or even what it's supposed to do.

Sorry to break it to you, fledgling developers of the world… this is the reality that we live in. Software development hasn't been a discipline long enough for all of this awfulness to be stamped out. You can help to fix this problem when writing new code, but for now you'll almost certainly have to delve into the dark underworld of legacy code.

Small bug fixes and changes may be possible without having a deep understanding of the code, assuming that the problems are well defined, but anything else will require some digging. If you're in any way like every other software developer I've ever met, you'll soon be fighting the rewrite urge.

Rewrites don't happen

A recent Dilbert comic nicely illustrates the familiar knee-jerk reaction of basically all developers to inheriting someone else's code:

It's certainly something I've witnessed on many occasions. Unfortunately for most developers… rewrites almost never happen.

There are many reasons why this is the case. Joel Spolsky's Things You Should Never Do blog post from April 2000 sums up the situation quite nicely and is still highly relevant today. Paraphrasing his mini-essay into bullet-point form:

- Weird things in code are probably bug fixes - throwing away code is throwing away the knowledge of problems encountered and fixed.

- Rewriting code is investing time in getting back to exactly where you already were, while everyone else moves ahead.

- It's entirely possible that you'll just make the same mistakes again.

Of course, individual pieces of code can be rewritten, but it's expensive and risky to rewrite entire projects. Sometimes products are superseded or replaced with new ones when technology evolves or requirements drastically change, but that's an entirely different thing.

Even in the rare situation where a rewrite is feasible, you still can't necessarily get away from reading and understanding the original code for anything other than the most trivial systems.

"Begin at the beginning"

"…and go on till you come to the end: then stop".

Directly quoting Alice in Wonderland seems appropriate, as the experience can be very much like falling down a rabbit hole, but the best place to begin is at the beginning, and by that I mean start with the requirements and documentation.

If no documentation is available, then you should write some - even if they're just notes to help you get your immediate job done, it's going to be an improvement on nothing and will benefit the next person.

Reverse engineering specific requirements (or edge-cases) can be quite tricky for older or larger systems, but most websites, web applications and certainly almost all phone/tablet applications are pretty self-explanatory, so you should be able to get the basics. It's also incredibly rare to be in a situation where there isn't at least one person to talk you through the basics of a system - someone must be using it, reporting a problem or requesting a change.

Most of the time you'll at least be able to discern the purpose and major use-cases from just playing around with the features. It's worth always noting these down just for the sake of clarity, as it's easy to get lost in the minutia and lose sight of the bigger picture. Personally, I would always aim to take one or more use-cases through end-to-end on a system that I am going to work on - and would try out as many as possible.

If you're working on an online application form, make an application. What are the validation rules and why are they like that? What are the constraints - minimum and maximum number of data items you can put in?

Once you've completed an application, find out what happens to it once it has been submitted. Is there an internal process or does it just fire off an email?

Consider the system outputs. For most systems developed at Fivium where I currently work, consent documents or licences are the ultimate result, generated as digitally signed PDFs. What should they look like? What data items make it through to the final documents and reports? What pre-processing or formatting steps do they go through?

These are the kinds of things worth knowing before you make any changes to any system.

There's a lot of cross-over here with exploratory testing. Talk to your testing team (if you have one) to get some ideas. Discuss with some friendly testers online if you don't have any within your company.

This leads us nicely on to…

Perform some tests

Most legacy code won't come with a test suite. Even the most diligent developers these days will likely not achieve 100% test coverage, and unit/integration tests in and of themselves don't get you that far. They protect the code against basic regression impact, but don't necessarily prove conformance to requirements or teach you anything new.

If there are few, or no tests, you should consider writing some. At the very minimum, if you're trying to fix a bug, then I would suggest writing a test that covers that scenario. At least then you have a (code) documented record of a problem that has been identified and you can use that to prove your fix.

If you have time, or are simply picking up a project as a new owner, it's definitely worth writing tests to explore the limits and assess the functionality. This can help act as useful documentation going forward.

Luckily, unlike with material archaeology, we can perform as many tests as like and the code won't degrade or fall apart, so there's really no excuse.

There's a great article over on the Fog Creek blog about how you can improve your test coverage.

Read and map out the code

This might seem obvious, but it's always tempting to read only the bits and pieces of code that are required to perform a change or fix. In my experience, this is one of the best ways to make a mess. Look for code units that you'd expect to see. Has someone already solved a problem that you need to solve? Can you reuse that code? It's incredibly easy to duplicate functionality in any non-trivial sized system, which will only make it worse to work on in the long run.

I always try to at least understand the core code units and how they fit together. Depending on the complexity, this may be worth drawing out in diagram form. If you're lucky, there may be tools out there that do this for you, such as Class Visualizer for Java.

At the very least you should perform an Impact Analysis - trace through what the effects of your change could be, and what other areas of code they affect. Your test coverage should be targeted at those areas as well as proving your intended change or fix. This often takes the form of a simple grep to establish where a function is called, but IDEs usually can do a better job and identify actual dependencies rather than just string matches.

Recreate history

It is thankfully very rare these days to encounter any software project that hasn't been stored in version control of some kind. At the worst end of the spectrum, you may encounter poor practise such as:

- No version control whatsoever.

- A different folder for development and production.

- Copying and date-stamping source folders for backup purposes.

- Use of backup tools or file-sync tools such as Dropbox that provide versioning.

- History stored only in IDE metadata.

If you're dealing with one of these, then you're frankly going to struggle to make any sense of what's there. If viable, you may want to migrate the source code and any version metadata into a version control tool. As long as you have the required metadata available, this isn't difficult, but may require significant effort.

In the worst-case scenario, you can at least commit the current code into version control without any history, so that you're doing things properly going forward. "Properly" means using a tool designed for the job, like Git, Mercurial, SVN or Perforce.

Learn from the past

The more common experience is that your software will be in version control and you can inspect the history of it. You're still dependent on whether previous developers have written good commit messages and committed code in sensible chunks, but any version control is better than none, and this is coming from someone who once had to use PVCS (shudder).

Looking at a raw commit log won't get you very far, unless you need only understand a few files or a few specific changes. There are a couple of great tools that can help (and are available for almost any version control system).

The blame tool

This is my favourite tool for code archaeology, by far. It gives you the immediate ability to view a file (at a given revision) and see how old each line is, who wrote it and what their commit message was, in-line with the file contents. This maximises the amount of context you have for understanding a piece of code and gives you a very useful overview of how a piece of code has changed over time.

You can see an example of GitHub's blame tool here: https://github.com/Fivium/jquery-tagger/blame/master/src/jquery.tagger.js

I deliberately chose a file that I've contributed to on another project, as most of my own projects have few contributors and revisions, so they're not a great example.

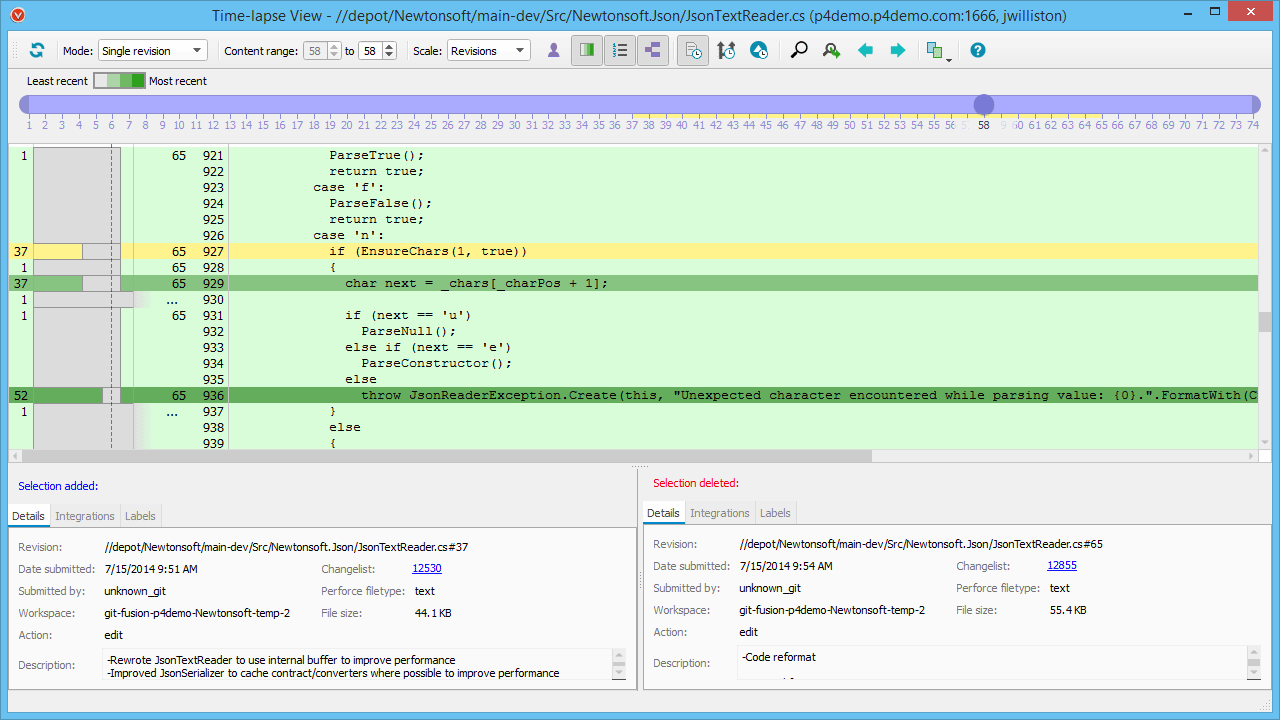

While most version control systems use the terminology "blame", Perforce's variant is much more charitably referred referred to as the time lapse view. It also takes the feature to its logical conclusion and makes it a full blown archaeology implement.

Perforce Time Lapse gives you:

- a little slider at the of the screen so you can easily switch to any revision of the file.

- code-age visualisations.

- the ability to see changes across branches (i.e. if a change was merged from another branch you can trace the "blame" back to its origin).

- you can show differences between any two revisions, at the same time as viewing the contextual "blame" information.

So, what can you learn from this tool? Although the name implies that we're seeking to blame a particular developer (or find out that the crappy code you're investigating was actually written by yourself), it's there to help you find out when and why changes were introduced, and where those changes fit in the overall history of the code's evolution. This is very useful when you find a bug that has been around for a long time, as it helps you understand what has been built on top of the offending change.

Perforce have a great demo video of the time lapse view in action, which I recommend having a look at.

Hopefully as I'm promoting awareness of their features, they won't mind that I shamelessly stole the screenshots from their website!

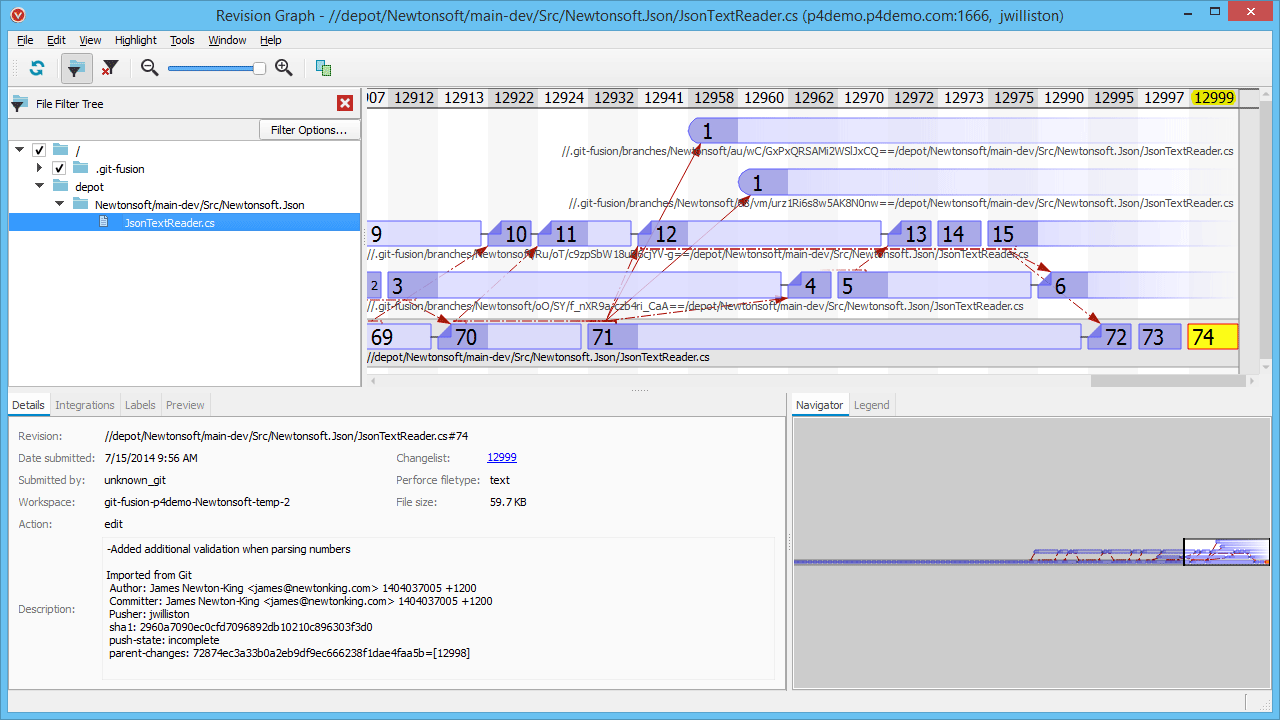

The revision graph

Revision graphs will give you a high-level picture of how individual files have changed over time. Hopefully this isn't news to anyone, as I think every popular version control tool supplies this kind of visualisation out of the box.

The true value is found in being able to see which branch changes were committed to and where commits have been merged subsequently. Why is this useful? It gives you oversight of where code is.

It's all well and good trying to reproduce a bug in order to fix it, but what if it has already been fixed by another developer and not released to production? You can make an argument for searching bug trackers for duplicate issues, but these are often easy to overlook and this sort of thing happens all the time. The revision graph will easily highlight this kind of situation; if you can see that your production branch hasn't yet received the latest commits, you can find out what they are and if it affects your work at all.

Another benefit of this tool is that you can understand how code came to exist in its current state. Did a change come from a feature branch? Was it an emergency bug fix? Has it been merged back from maintenance on a release build? Finding out this information becomes simple when version control is visualised.

Perforce comes with a great tool for this, which as per the heading above, it calls the Revision Graph:

For comparison, this is the one bundled as part of the commit "Log" viewer in SmartGit:

Code reviews

If your company uses tools such as Crucible or Review Board for code reviews, then you may find a wealth of information in there. At Fivium, we use Crucible as our code review tool with the primary aim of improving quality, but it has a secondary benefit of being automatic documentation of questions and decisions.

We'll often ask each other questions such as "Why is this line of code like that?", "Have you considered these edge-cases?"… There's no perfect place for this type of commentary to exist, but the dialogue that naturally occurs during a peer code review is extremely helpful narrative, and if you tie together revisions of a file with the reviews that it's been involved in, you can glean some very useful information that may have otherwise been a verbal discussion or stuck in a text file on someone's computer.

Of course, code reviews can go beyond changes that are occurring now, it can be well worth kicking off a code review to retrospectively examine a piece of code, and collaborate on understanding it. Crucible lets you do this at any time, and you can easily annotate on a line-by-line basis, raise new issues in your bug tracker and so on. Being able to review a cross-section of the code, alongside other developers and stakeholders, and ask questions on a line-by-line, method-by-method or class-by-class basis is very helpful.

In summary

I hope this has given you some insight into the challenges that you'll face sooner or later as a programmer in the real world, and the tools that can assist you.

Always remember that whatever fresh, new idea your company is working on today is next year's legacy code, and once you've experienced Software Archaeology, you'll hopefully try to stop it being a necessary practise for future developers!